Carlo Giovannoni was a versatile artist from La Spezia, where he was born, lived and worked his entire life as a painter and sculptor (read his biography here). Today we have the pleasure of chatting with his daughter, Fabrizia.

Carlo Giovannoni began his activity as a self-taught artist, and when he was just 14 old he became a student at the workshop of master sculptor Del Santo. How did he approach art in his childhood? What pushed him towards sculpture and painting?

The loss of his mother, Caterina, when he was just one year old, and the consequent lack of that figure, marked the life and choices of my father and his sister Pia. The complicated relationship with the father (who had a very different character) and the new wife led to suffering and insecurities, and so taking refuge in art was natural and vital for him.

A paternal aunt acted as their mother, but while the sister was sent to boarding school, Carlo began violin studies and the sculpture school under the fine guidance of Maestro Del Santo.

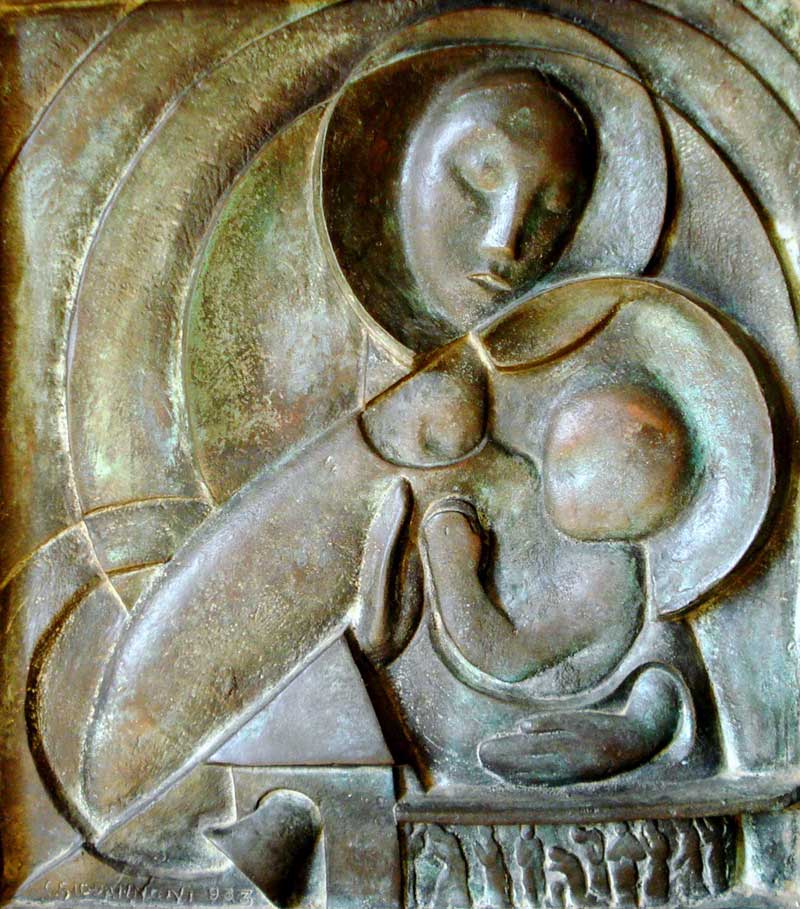

This is what has been written about him: “(…) Giovannoni, already in 1935, exhibited in Genoa at the Rassegna Nazionale Sogni di madre; in 1937 in Palermo at the Youth Exhibition; in 1938-39 at the Interprovincial Trade Fairs and in 1942 at the Exhibition of Italian Artists in Arms.”

Painting at that time was more ‘scholastic’. Portraits and landscapes were the themes that inspired him most when he returned to Lunigiana, the land of his paternal grandparents. His albums of studies and sketches in pencil and/or pastel are interesting, because you can see the beginnings of his artistic career.

The military service and the years of war as stretcher-bearer interrupted his artistic projects, he was worn out and emptied. Finding some friends in the rubble of the city triggered my father’s desire to ‘relive’: new research began, new enthusiasm, new moments of encounter and he joined the famous ‘Group of the Seven’ among other artist groups.

With a new awareness and having overcome many challenges, at the age of thirty he decided that art was his life at the cost of sacrifices and that a family was now an absolute requirement: today mom and I are here to remember him and to let others know about Carlo Giovannoni.

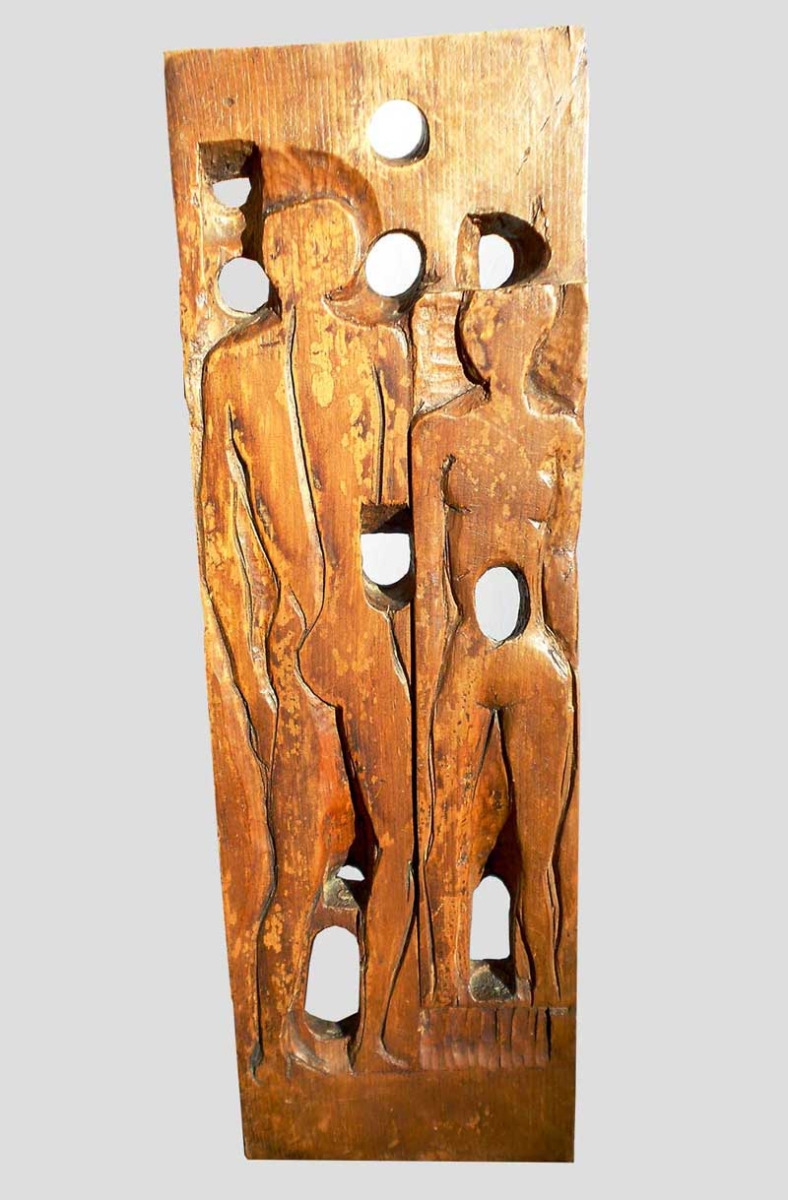

In the 1920’s and 1930’s, Carlo Giovannoni devoted himself above all to sculpture, in the post-war period he began to work even more on painting, and from the ‘60s onwards he created numerous wooden artworks. What similarities or differences are there between his works of plastic art and paintings?

The question is interesting, I prefer to compose the answer with excerpts of comments by some authoritative critics who can give interpretative ideas on my father’s long artistic journey.

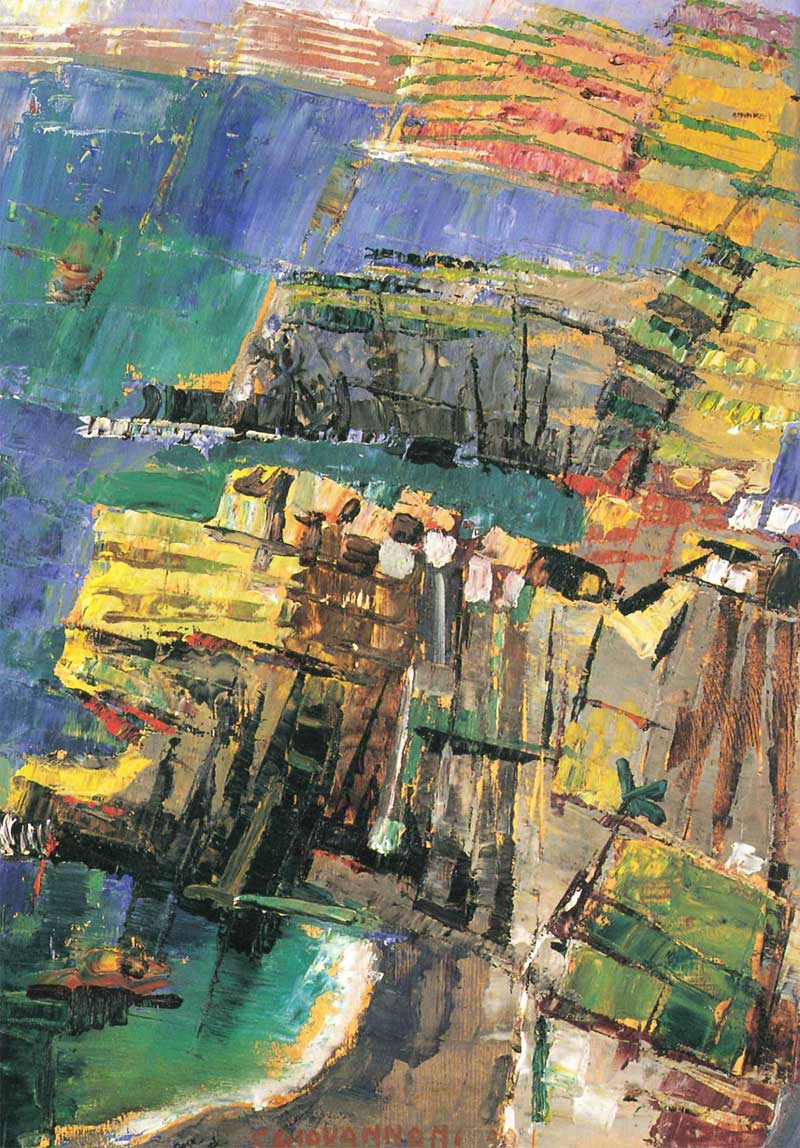

In 1984, art critic Renato Righetti wrote: “He loves the two arts with equal momentum, but perhaps sculpture – even if he is more reluctant to admit it – has always exerted on him a more pungent appeal, an irresistible charm derived in the years of the first formation with Angiolo Del Santo. […] His painting is somehow linked to his sculptural work, and this is an obvious fact to those who are able to approach his paintings by savoring their expressiveness in full, penetrating their structural reality full of relationships between matter, form and content. […] The Cubist lesson and that of abstractionism (in the short but intense experience with the Group of Seven) have had profound resonances on his work, more deeply internalizing his art and promoting its leap in quality towards a clearer connotation of its identity.”

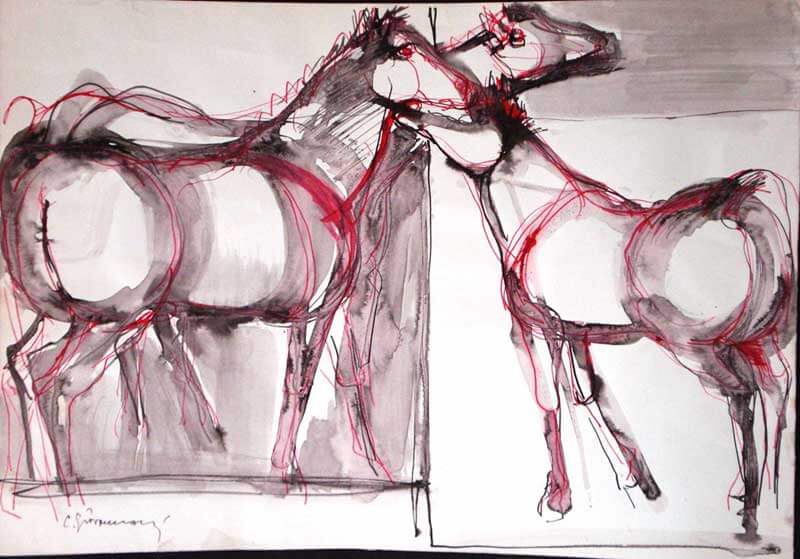

In 1990, art critic Ferruccio Battolini said: “Giovannoni was a painter and sculptor who – from the pre-war period to the golden age of the ‘Group of Seven’, from the brief moment of the ‘La Spezia Group’ to the long cycle of landscape compositions of Cinque Terre, from the years of significant sacred art works to the beautiful ink drawings – he always testified to his loyalty to invention and to a keen sense of the so-called “different truths”, consistent within a visual heritage, vigorous and delicate at the same time, full of intuitions and of concrete poetry, of free yet supervised imagination. A visual heritage born from simple and conspicuous ‘primary feelings’ which in turn support every type of formal organization and above all the many ‘real entities’ that he always strongly and generously offered. “

In occasion of Hamburg’s Mensch Atelier Show in 1974, Hanns Theodor Flemming, art critic at Die Welt, wrote: “Carlo Giovannoni owns a very high degree of virtuosity, quite often his subjects represent horses and riders that man wants to dominate. Such coloured Indian ink graphics, the colours one upon the other and alternatively the spray technique, give his works a high degree of effectiveness showing his great skill. In his paintings, main themes and shapes move within the range of classic and the best-known modern expressions, giving movement dynamics and thrilling brightness to his work“.

Carlo Giovannoni also ventured into the world of amateur cinema as a director. What stories did his short films tell?

Cinema and photography? For Carlo Giovannoni they were a great passion and also a way of enriching his research on lights and colors that we find in his pictorial and graphic works of the years that followed. Availability was very scarce so he took care of all the technical parts by himself in all the films that he shot at 16 mm: he built the trolley for the movement of the machine and the reflectors, he edited with a monocle frame by frame, he was camera operator, handled the sound effects and also the writing of titles. Just for some scripts, he sought the help of friends. These were the rituals that he carried out annually to present a new proposal at Montecatini’s amateur film review: our home was all about amused helping friends who came and went.

His short movies spoke about the territory and its people. For example, “Ettaro di mare” is a color documentary of the late 1950s, a precious tribute to the hard work of the mussel farmers. It is an important story because it captures moments, techniques and places that soon changed and disappeared. It was shot in La Spezia, where houses on stilts still existed in Fossamatra, and in Portovenere, where large mussel farms produced an excellent product exported everywhere. The short movie participated in various events and won as best documentary, best photography, and was chosen by an international jury for a festival in Helsinki. Another acclaimed work was “Nicolino”, set in Manarola (Cinque Terre) and awarded for best photography. The protagonist is a young boy, Nicolino, played by Albino Faggioni who also won awards for his performance. Giovannoni appears in some scenes … perhaps an identification with that child who was so soon destined for the works of adult life?

And there is also “Gente nostra”, which narrates the hard life of men and women dedicated to the cultivation of a few square meters of non-generous land: a life that involved the older generation deeply linked to that reality, but discouraged the youngest ones looking for easier achievements.

Image critic Claudio Bertieri wrote in 2004: “Carlo Giovannoni was one of these generous “do it yourself” filmmakers who did not like social status classifications, much less the rules imposed by habit or, worse, by the current consumption of the film. Cinema, his at least, had to be “useful”, in the sense that it was intended to document, provide testimonials, make a careful report. […] His films convey feelings and emotions that have certainly not aged or withered. They show moments of peasant or seafaring life mixed with pride and awareness, ancient virtues of people who express a deep bond with the local territory, without the need of words.

You can watch Carlo Giovannoni’s videos on www.carlogiovannoni.it.

What does it mean to be the daughter of Carlo Giovannoni?

…. Being here suspended between narrating the life with an artist father and the desire not to say too many words for the risk of falling into rhetorical obviousness.

Certainly, he was a rigorous father but an irresistible ‘dad’ who, in the continuous exchange of these two roles, never put himself in the teaching chair: dialogue was always a fruitful mutual confrontation. He had an extraordinary character, he did not hide the ‘normality’ and the limits of daily life, with his grace and his discretion he managed to be liked by everyone.

I have already said enough even if his long history deserves to be told.

I would only add that the many benevolent comments and memories of those who knew him, have convinced me in recent years that it was my duty to keep his figure and his work alive.

Of course, times are difficult: the paintings and sculptures that now ‘surround’ me should live of space, light and right encounters … my task is not finished yet….

Where can you see Carlo Giovannoni’s works?

The works are at the Giovannoni Studio in Gallipoli (Apulia) where we now live. Some works of art are exposed around Italy, for example at the Grand Hotel Portovenere in the Gulf of Poets – La Spezia.

Discover more from Discover Portovenere Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.